Local meetings held, committees formed to oppose Fugitive Slave Law

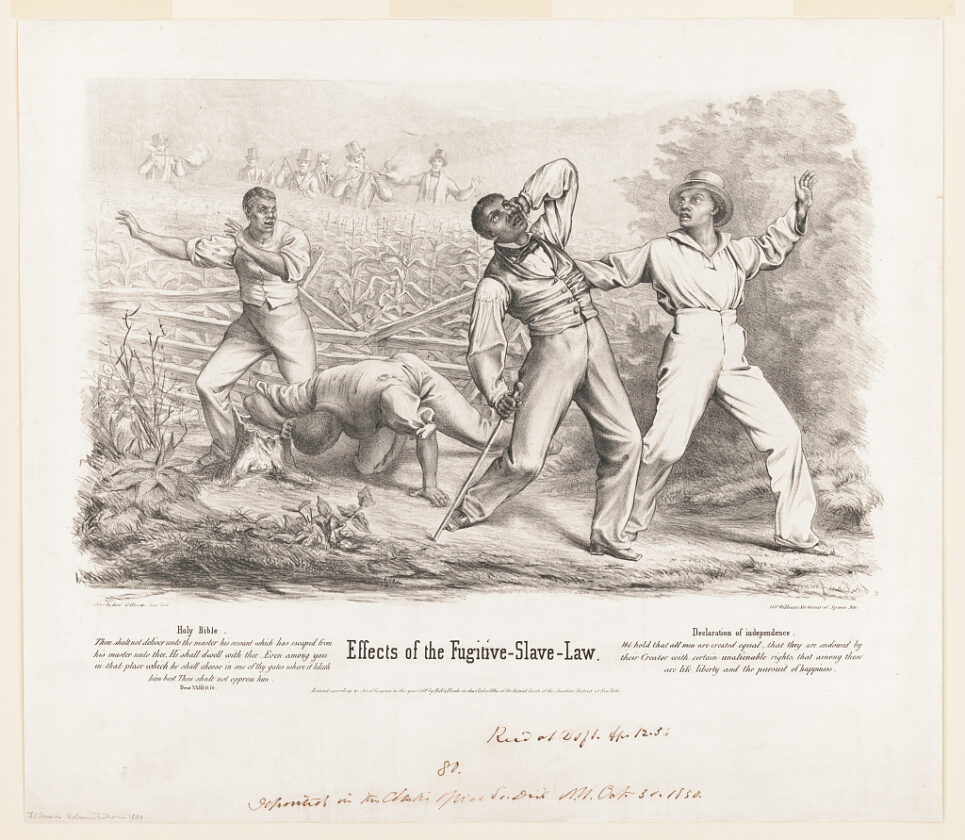

Library of Congress image This rendering of an enslaved person being recaptured entitled “Effects of the Fugitive Slave Law.” The Bible and the Declaration of Independence were invoked in the design.

It seems counter to our modern sensibilities that an act of Congress would cause public meetings, establishing committees and strong public statements in Warren County today.

Such was the case in the fall and winter of 1850.

The issue was one that had plagued the country since before its birth – sectional disagreements almost wholly rooted in slavery and its potential expansion.

While we have the hindsight to see that the nation was hurtling toward Civil War, that was still 10 years down the road when the Compromise of 1850 was agreed to.

According to the National Archives, the compromise was really five separate statutes enacted in September

“The acts called for the admission of California as a ‘free state,’ provided for a territorial government for Utah and New Mexico, established a boundary between Texas and the United States, called for the abolition of slave trade in Washington, DC, and amended the Fugitive Slave Act,” their article explained.

“The bills provided for slavery to be decided by popular sovereignty in the admission of new states….”

Popular sovereignty… the idea that a state’s citizens would get to pick whether their state was slave or free. It’s a nice idea in theory but in the broader construct of the government, it was doomed to failure. The competing interests were too strong.

There was an awareness in the South that if too many states went free, the equilibrium in Congress would shift. Would a free state-dominated Congress launch an assault on slavery?

In the north, the abolition voice was growing. Slavery could be preserved forever if enough states – and their allocated representatives and senators – came into the Union on the slave state side.

The compromise was designed to balance those competing sectional interests.

But one piece of the compromise literally crossed that line – a beefed-up Fugitive Slave Law.

The idea of a law designed to allow slave holders to recapture escaped slaves wasn’t new. That dated to the country’s founding.

The change in 1850, though, were what drew the outcry.

Again, per the National Archives, the amended Fugitive Slave Law that was part of the Compromise of 1850 required citizens to assist in the process and “denied a fugitive’s right to a jury trial.

“Under the Fugitive Slave Law, an accused runaway stood trial in front of a special commissioner instead of a judge or jury. These commissioners were paid $5 if an alleged fugitive were released. They received $10 if the fugitive was sent away with the claimant.”

The incentive structure embedded there in the law could not be more clear.

The law also required local and federal law enforcement in all states – not just slave states – to “enforce the legislation and arrest suspected fugitive slaves,” per the National Archives.

On top of that, anyone assisting enslaved people in their escape was now subject to criminal prosecution.

“The Act was broadly condemned in the North and prompted multiple instances of violent resistance,” according to the National Constitution Center. “Although the Supreme Court upheld Congress’s power to pass such laws in Prigg v. Pennsylvania, Northern states resisted enforcement of the law on their soil.”

That condemnation in the North resulted in multiple public meetings held in Warren County.

At the heart of one meeting was James Catlin, part of the Catlin family known for the abolitionist views, and one of the people in Warren County who corresponded directly with Frederick Douglass.

The meeting had been sent to “discuss the bill” and a committee prepared a series of resolutions – or statements – “which after considerable discussion were sustained by a very large majority of all present.”

“Resolved, That the age is now past for any compact, bindung us to replunge men into slavery after their manful escape – to claim any respect or observance at our hands,” that group concluded. “For nearly sixty years we patiently submitted to the infamous act of ’93.

“Our submission only emboldens the oppressor.”

They were particularly opposed to the responsibility the law placed on citizens to help catch these people.

They called the “most odious feature of this bill is that it makes slave catchers of all of us. I

“It is less degrading to be compelled to force others to be slaves. Of the two evils, we will choose the lease, wear the bonds ourselves instead of fastening them on others.”

The financial incentive structure then came under their attack: (T)he provision giving the commissioner ten dollars if he decides one way and only five if he decides another, is an insult – not only to the tribunal but to the whole Northern people, and to Human nature itself.

“(I)t is in our opinion an open, unblushing, legislative attempt at bribing by means of a five dollar bill.”

They called on the county’s clergy to stand up in opposition to the law: “the Clergy of all denominations inasmuch as they are the watchmen upon the walls – the ambassadors of Him who came to bind up the broken hearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives and the opening of the prison to them that are bound and inasmuch as they are our public Religious Teachers, set apart and ordained to the work of teaching us our duties to God and man – are imperatively called upon in this crisis to lift up their voices like a trumpet in reprobation of all who frame mischief by a law and in declaring their supremacy of God’s law over all Human enactments.”

One pastor, a “Rev. H. More,” presented a resolution that struck a chord for liberty: “That as loyal citizens of the United States law-loving and law abiding – admiring the sentiments set forth in the declaration of independence; and the spirit of our institutions – we feel compelled to oppose and resist the spirit and letter of the fugitive slave law inasmuch as it is wholly opposed to our liberties, our honor and the secured interests of the entire country both at home and among the other nations of the earth.”

Given what we know would follow in the years and decades after this meeting, it’s easy for us to look at this opposition as one of many inexorable steps toward civil war.

While some may have seen some kind of conflict on the horizon, it would have been impossible to foresee what that war would turn into.

In short, the opposition to the Fugitive Slave Law was not unanimous.

A second meeting had been held shortly after the bill’s passage in Conewango Township.

“We believe there are other subjects which now vitally concern the interests of the county at large, and particularly this county, than the fugitive slave law,” these men concluded.

“That however exceptional and offensive to the feelings of humanity that law may be, as some of its provisions certainly are, we can see no good to result from its agitation at the present time as it is useless to ask the same Congress which passed it to repeal it.”

That’s a fair criticism, honestly. Why would the same Congress that enacted the bill change course months down the line?

That meeting’s resolutions called for action on tariffs and other economically-related issues.

“But there are other laws, both State and NationaL, which are actually enslaving us who profess to be free, and which might with a moiety of the effort and zeal manifested in opposite to the slave law, be repealed or modified.”

So American politics continued… on a decade-long march to the Civil War that few could have imagined in 1850.